True Blue – Authenticity and Yalumba’s Value Chain

Cecil Stephen Camilleri

The Yalumba Wine Company, Australia

History, Tradition and Environmental Good Practice – An Introduction to The Yalumba Wine Company

The history of Australian wine, and perhaps its future, is closely associated with Britain’s love affair with good quality wine (Beeston 1994; Johnson 1992). In fact, in a paper presented in 2007 at the international conference on corporate communications held at Wroxton, Dr. Cecil Camilleri of the Yalumba Wine Company described wine as a socio-symbolic artefact – a cultural product replete with symbolism and meaning (Camilleri 2008a). Yalumba’s links with Britain date back to 1849 when Samuel Smith, a brewer from Dorset, settled his family in the free State of South Australia and planted 30 acres of vineyard (Linn 1999). This was the simple foundation of Yalumba. Six generations and more than 150 years later Yalumba, Australia’s oldest family owned winery, has developed into a wine success story, basing its sustainability on stakeholder relationships as well as the careful management of the essential elements that make wine – principally, earth, air, water and energy.

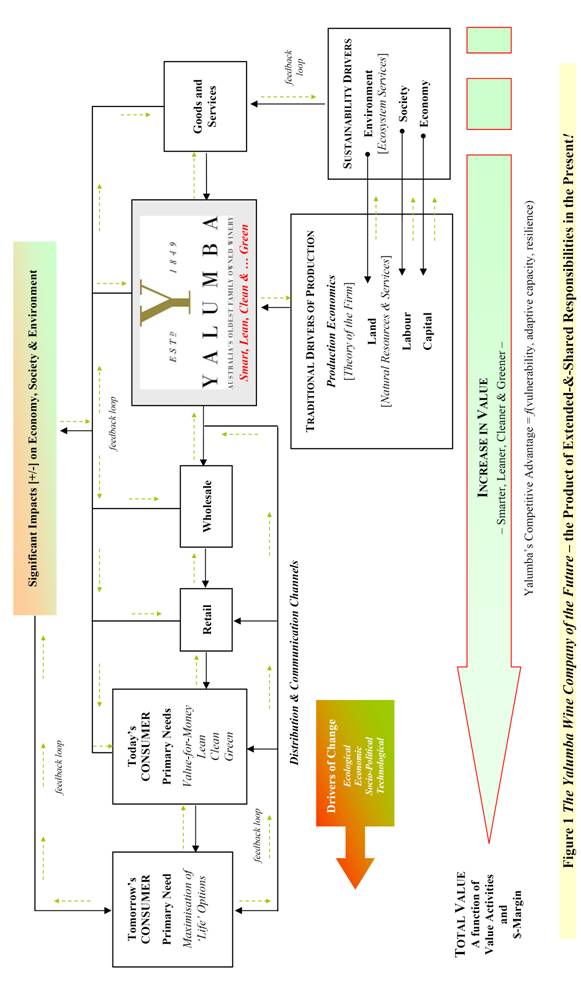

Yalumba’s environmental programme is composed of five key performance areas, which it refers to as the five pillars of sustainability: land stewardship; product stewardship; climate change mitigation and adaptation; waste management and environmental citizenship. These sub-programmes were designed to conserve and protect Yalumba’s natural resource base and to engage the organisation’s stakeholders in similar activities. In fact, Yalumba is of the firm opinion that a low-carbon future requires a constructive dialogue between all members of the supply chain. The product of this dialogue can be a sustainable value chain – one that emphasises long-term, significant economic return to all members of the supply chain, particularly to those that follow business practices that use the highest standards of environmental and social stewardship (figure 1). But this is easier said than done. Environmental sustainability poses a significant communication challenge. Each of Yalumba’s stakeholder groups has a different level of perception, knowledge, interest and attitude towards the environment. However, to address issues of sustainability effectively, holistic and co-ordinated actions by several stakeholders are needed, which requires communications and cooperative behaviours. Consequently, each stakeholder group needs to be approached in a unique way. This highlights the most important aspect of Yalumba’s external communication – the ‘linkage-mix’, or the company’s network of formal and informal relationships, both professional and non-professional.

By strategically ‘sharing’ Yalumba (Camilleri 2008a), the organisation is targeting the creation of trust, enhancement of reputation and competitive advantage. But this can only be achieved through customer and stakeholder knowledge, differentiation, relevance and esteem. This led Professor Andrew Fearne, director of the dunnhumby Academy of Consumer Research and the Centre for Supply Chain Management at the University of Kent, to concede that whilst the Yalumba story is compelling, the challenge is to turn the narrative into sustainable competitive advantage, particularly when many of the wine firm’s distinct characteristics are credence attributes (pers. comm. 29th July 2007). In effect, Yalumba needs to match the channel of communication with the message and the targeted stakeholder group. To put it another way, the wine firm must determine the most effective means of communicating what to whom. Furthermore, Yalumba must clearly articulate the governance mechanisms that it possesses as well as the attributes that makes it ‘true blue’ in order to convince stakeholders of the benefits that emanate from delivering on the promise[1].

|

The Promise! – Yalumba’s Commitment to Sustainability

As a family-owned, true-blue organisation that has been operational for over 150 years, the values of The Yalumba Wine Company have evolved to address business and lifestyle demands in a carbon-constrained future. Its values are expressed through its passion for winemaking and grapegrowing, quality of life, family-based ideals and a commitment as well as dedication to the conservation and long-term sustainability of the environment.

Through its employee-stakeholders, Yalumba is proudly committed to the pursuit of continued sustainability and best management practices in all spheres of its business activities. It aspires to be a smart, knowledge-based, independent wine company with the necessary adaptive capacity and resilience to succeed in a globalised competitive wine-market that will increasingly be impacted by climate change, and where the consumer, and other stakeholders, will be at the centre of concern for sustainability. Through its ‘Commitment to Sustainable Winemaking’ programme, which is a whole-of-company, life cycle approach to environmental management, Yalumba leaves nothing to chance when it comes to protecting the essential elements that make up wine – air, water, soil and energy (Camilleri 2000; 2003; 2008b). Robert Hill Smith (2007a), proprietor and managing director of The Yalumba Wine Company, comments that by sharing its hand-crafted wines with the world Yalumba believes it is also sharing the responsibility of protecting the future. Hill Smith adds that after six generations of family ownership at Yalumba, the future is as important to it as the present.

As a corporate family, Yalumba and its people (that is, its community of employees) strive to practice good environmental stewardship. By taking responsibility for continuous improvement within Yalumba’s sphere of influence, a multitude of minor changes have resulted in significant and positive environmental improvements – including those aspects that have a direct impact on the process of climate change (Camilleri 2008b). These improvements, particularly those in the area of good housekeeping, have not only led to efficiencies in production and legal operation but also have also contributed to a healthier, and safer, work environment. Ostensibly, if these benefits flow on to consumers they will not only protect current market share but will also allow Yalumba to take advantage of opportunities in the market place (Camilleri 2004). In other words, good environmental stewardship is recognised by Yalumba as an essential component of a quality-focused work environment and sustainable competitive advantage. Through an ecosystem approach to land management (Camilleri 1998; Camilleri et al. 2000) and by achieving ‘more with less’ the wine firm guarantees the conservation of resources and the protection of ecological processes.

Yalumba and its community of employee-stakeholders continue to reset ‘the compass’ by benchmarking themselves against stakeholder performance and expectations. By doing so, Yalumba aims to maintain relevance without compromising future options and its ineffable sense of place (Camilleri 2008b). Through strong governance, this authentic commitment to social, economic and environmental responsibility is expected to yield sustainable competitive advantage. Yalumba’s commitment to sustainable winemaking ensures its continued existence as “… an independent-thinking, innovative, courageous fine wine maker with integrity … doing a lot of things that aren’t yet evident ... that [come] out of being family-owned as well as patient, visionary, supportive, energetic and employing intelligent people.” (Hill Smith 2007b).

In keeping with the principles of sustainability espoused in 1987 in the Brundtland Report, Yalumba is committed to:

- Demonstrating a high standard of due diligence and corporate citizenship.

- Producing quality grapes by creating a balanced vineyard ecosystem that makes efficient use of natural capital, stems environmental decline, regenerates resources and promotes environmental health and safety.

- Demonstrating extended and shared producer responsibility through continuous improvement in packaging waste reduction and management.

- Minimising the emissions of greenhouse gases throughout the life cycle of wine.

- Setting aside land for biodiversity conservation and carbon sequestration.

- Achieving high levels of eco-efficiency by using environmental resources more efficiently, thereby reducing ecological impact and resource intensity throughout the life cycle of quality wine.

- Promoting amongst stakeholders a better understanding of environmental issues as a basis for responsible environmental action, and to enable the environmental objectives of key stakeholders to be achieved.

- Producing wine brands that authentically echo Yalumba’s sense of place in the global social, economic and environmental milieux.

This is Yalumba’s covenant (psychological contract[2]) with present and future stakeholders[3]. By committing to these principles The Yalumba Wine Company is affirming the following interconnected characteristics of authenticity:

- Acting in one’s own authority;

- Being truthful to one’s self;

- Achieving congruence between beliefs and communication; and,

- Being distinctive and coherent.

When a bottle of a Yalumba brand is opened and the genie is let out of the bottle, the consumer is granted three wishes: value for money, commitment and trust.

The Meaning of Authenticity

As a community of employees, Yalumba is beginning to realise that authenticity is an established component of contemporary life (Grayson and Martinec 2004). To the postmodern consumer authenticity primarily means being trustworthy, in the sense that an organisation should act in line with its brand values and behave as a citizen of the community. Of the firms that are able to produce brands as ‘original cultural materials’ (Grayson and Martinec 2004), consumers will increasingly weed out those that they do not trust. As consumers peel away ‘the brand veneer’, they are looking for companies that behave like a ‘local’ firm – in other words, like a respected citizen of the community (Holt 2002). Undoubtedly, the demands on more corporate social responsibility and ethical behaviour on the part of brands are very high in contemporary ‘First World’ society[4]. This will require The Yalumba Wine Company to be clear about its sense of what ‘authenticity’ means to it. To that extent, dialogue as well as listening to what critics have to say about a particular brand will provide Yalumba with important insights on how it is understood by the consumer (Gustafsson 2006). Moreover, the postmodern consumer does not have the time to construct his or her identity as the old definition of the ‘sovereign consumer’ advocated[5]. In contemporary society, brands are relied upon to help consumers feel in control. Lack of time to exercise active, reflexive choices makes the consumer increasingly reliant on popular literature and other sources to decide which brands constitute a responsible purchase. It is here argued that the need to rely on brands to do this makes trust an even more important topic within the current (and future) branding paradigm, particularly since it is not easy to differentiate between reliance and trust. Baier (1986) defines trust as ‘reliance on another’s good will’, which implies that reliance and trust are interrelated, and good will must be sufficiently strong to ensure that the trusting person is not abused. This effectively means that the less time there is for consumers to choose for themselves and evaluate the trustworthiness of certain brands, the more important it is for brands to be authentically trustworthy. The new market reality is that ‘brand veneer’ is worthless if it is not combined with genuine efforts to demonstrate to stakeholders that a brand’s values are a reflection of the excellent practices and values of the firm behind the brand. Therefore, the current branding paradigm requires brands to be ‘citizen-artists’ (Holt 2002) that recognise,

- Authenticity as being all about trust from the consumers’ point of view; and

- The need for convergence between brand values and organisational practices.

In short, making organisational actions transparent, aligning brand values with organisational values, and communicating that the brand is a good citizen, are necessary steps that Yalumba must take to demonstrate trustworthiness and willingness to engage in trust relationships with consumers and members of the value chain alike. This is the journey of the discovery of what it means to be authentic (Gustafsson 2006).

Arguably, and perhaps contentiously, the future of The Yalumba Wine Company is not exclusively about selling, but primarily about building relationships (McCrindle and Beard 2007). With respect to communications, discrete messages to distinct stakeholders are no longer possible, because in today’s dynamic marketplace information moves across audiences. If Yalumba accepts this argument, it must use multiple channels of engagement to reach its target audiences, and draw on different sources of information to shape perceptions. Edelman (2003) advises that organisations must reach all stakeholders with the same story in a timely, accurate and credible manner. To achieve this effectively, Yalumba must create a ‘master narrative’ that clearly articulates the ideals that extend through all its internal operations and external relations. Furthermore, it must increasingly come to the realisation that there is strength in sharing its knowledge (or lack of it) with its stakeholders through ongoing frank and open dialogue. The smart company understands that external stakeholders and employees do not demand perfection. In fact a smart organisation builds its reputation from inside out by engaging employees as advocates and by establishing dialogue with the consumer as well as members of the supply chain. By doing this, Yalumba will create an experience that deepens the relationship with its value chain.

Increasingly, connecting with 21st century consumers requires Yalumba (together with its value chain) to be socially connected; fun and entertaining; life-enhancing; innovative; and socially desirable. More than ever before, Yalumba must be grounded in a confident sense of what defines it – why it exists, what it stands for, what does it value, and what differentiates it in the marketplace. Discovering the answers to such questions and embedding them in real and lasting ways into the fabric of the whole value chain is a strategic challenge. To address this challenge Yalumba has partnered with the dunnhumby Academy of Consumer Research, key members of its value chain, tertiary institutions and instrumentalities of the government of South Australia to analyse the value received by the consumer when a Yalumba brand is purchased. The key to this action research, which is being undertaken under the auspices of the Adelaide Thinker in Residence (ATIR) programme of the Government of South Australia, is to reinforce authenticity and relationships along the value chain[6]. Yalumba’s journey of discovery has thus reached another milestone in its history.

‘Vine to Dine’ – A Case Study of Authentic South Australian Wine

The Yalumba case study, which commenced in May 2008, is funded by in-kind contributions from participating industry partners and universities and a research grant sourced from Primary Industries and Resources South Australia (PIRSA). One of the principal objectives of the project is to highlight sustainable value stream mapping as a tool for adopting best practice in sustainable value chain management (Bonney et al. 2007). It is further anticipated that the research outcomes will act as a catalyst for change and as a mechanism for achieving better alignment between the allocation and utilization of resources in the South Australian wine value chain and consumer preferences in the United Kingdom. The latter is one of the principal export markets for the South Australian wine industry (Australian Wine and Brandy Corporation 2008). In addition, this project will:

- Assist the South Australian wine industry to develop a constructive partnership with Tesco to address the supermarket’s aspirational targets of carbon labelling and the adoption of a more consumer-focused approach to the development of the wine category (Leahy 2007).

- Demonstrate the benefits of collaboration between members of the whole value chain, particularly in the area of co-innovation (Hlupic and Qureshi 2003; Global Commerce Initiative, Capgemini, Intel 2006).

- Produce a case study to help promote the principles of sustainable value chain analysis across the Australian wine industry and other value chains within the South Australian food industry.

- Significantly contribute to the achievement

of several targets outlined in South Australia’s Strategic Plan (Government of

S.A. 2007a), namely:

- Targets 3.5: Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reduction and 3.7: Ecological Footprint – The project will provide a methodology that can be used by the South Australian business community to understand the impacts of climate change on commercial operations, guide mitigation and adaptation initiatives, and facilitate the establishment of Sector Agreements under the South Australian Climate Change and Emissions Reductions Act 2007 (Government of S.A. 2007b).

- Target 1.14 Total Exports – The project is expected to contribute to South Australia’s export income through promotion of South Australian wine in the United Kingdom.

Methodology

Value chain analysis (VCA) and life cycle analysis (LCA) will be the methods of choice to map the wine value chain from South Australia to the United Kingdom, combining analysis of information flow, material flow and supply chain relationships with a detailed life cycle assessment from the vineyard to the consumer’s table (Camilleri 2008b, 2008c).

VCA is a diagnostic tool that was originally developed (Porter 1985) to support the application of ‘lean thinking’ (Womack et al 1990). It is defined by Taylor (2005) as, “… the multi-dimensional assessment of the performance of value chains including the analysis of product flows, information flows and the management and control of the value chain.” The project will utilise a VCA-variant developed by Prof Andrew Fearne and his team at the University of Kent to assess the quality of the backward and forward linkages in a value chain, particularly those associated with the flow of products, communication and stakeholder relationship or trust (Fearne 2008). As stated earlier, the research will adopt The Yalumba Wine Company as a case study to explore strengths, weaknesses, constraints and opportunities for sustainable competitive advantage through collaboration between members of Yalumba’s value chain. The key to this form of participatory value chain and market development is to reinforce linkages and partnerships along the chain. Importantly, the participating stakeholders must be willing to adopt a learning approach in order to create an environment of co-innovation.

Tools typically used during a participatory value chain analysis include key informant interviews, focus groups, questionnaires, and participant observation. Importantly, members of the value chain are recruited to collaborate in the researcher process, which is based on five typical action areas, namely:

- Selection of sector and value chains.

- Value chain mapping to trace product flows, show value additions at different stages, to identify key stakeholders and their relationships in the chain.

- Consultations with lead firms and other chain stakeholders.

- Participatory value chain analysis.

- Stakeholder validation and planning workshops.

The tools and methods used need not be sequential. In fact, it is not unusual for activities to be undertaken in parallel.

In addition to the organisational perspective, it is anticipated that the research will also explore the general condition of the wine industry’s value chain by conducting a survey of industry players, including grapegrowers, winemakers and suppliers of goods and services. This aspect of the research will be undertaken in collaboration with industry bodies, including the Australian Winemakers’ Federation of Australia.

LCA, or life cycle analysis, is often called ‘cradle to grave’ analysis because it encompasses all the activities associated with the extraction and processing of raw materials, the manufacturing, transportation, marketing and use of a product, as well as the disposal or recycling of by-products. The method is a systematic approach to measuring resource consumption and environmental releases to air, water and soil associated with products, processes and services (Jensen and Remmen 2005). However, in contrast to VCA, the focus of LCA is on the intensity of resource use and the environmental impact of outputs at each stage of the value chain. The research will explore the value-adding opportunities of life cycle analysis through the provision of information on greenhouse gas emissions to Yalumba’s value chain. It is envisaged that, for the purpose of this study, several LCA standards will be explored, including:

- Greenhouse Friendly™ – a carbon labelling protocol and accreditation programme developed by the Australian Government’s Department of Climate Change (Australian Greenhouse Office 2006).

- The ‘PAS2050: Specification for the Assessment of the Life Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Goods and Services’, which is being developed jointly by the Carbon Trust and the UK Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Carbon Trust 2008). It is noteworthy that PAS2050 is not only currently being piloted by the supermarket chain Tesco in the context of their carbon labelling initiative but is also expected to become the internationally accepted protocol.

- The ‘Greenhouse Gas Accounting Protocol for the International Wine Industry (version 1.1)’ developed by Provisor Pty Ltd and The Yalumba Wine Company (Forsyth et al. 2008) – The protocol was co-funded by Winemakers’ Federation of Australia, the Wine Institute of California and industry partners in New Zealand and South Africa. The protocol is now an essential component of the proposed Climate Change Sector Agreement between the South Australian Wine Industry Association and the Government of South Australia.

The costs associated with environmental labelling will also be identified.

Conclusion

In the foregoing, this author has argued that an authentic organisation is one that generates profits through the cultivation of trust and the pursuit of a profound and positive purpose. Ostensibly, this is what imparts competitive advantage to the authentic organisation and added value to the consumer. In a globalised business environment ‘authenticity’ is nothing less than extended and shared corporate responsibility. The ‘vine to dine’ project, which is currently under way and is scheduled for completion by November 2008, aims to explore this business paradigm by bringing together a unique combination of government, industry and academic expertise in complimentary aspects of value chain analysis and life cycle assessment. The project is under the general supervision of Professor Andrew Fearne who, as the current ATIR, is also responsible for overseeing the research that is being undertaken by the dunnhumby Academy of Consumer Research at the Kent Business School. Dr Claudine Soosay of the University of South Australia and Mr. Ben Dent, senior researcher at the University of Kent, are leading the value chain analysis. They are assisted by David Henderson (Department of Trade and Economic Development), Annabel Mugford (Primary Industry and Resources South Australia), Glen Ronan (Primary Industry and Resources South Australia) and Monika Stasiak (Zero Waste South Australia).

The life-cycle analysis is based on the work already undertaken by Dr Cecil Camilleri of The Yalumba Wine Company (Camilleri 2008b). Professor Randy Stringer and Dr Wendy Umberger, both from the University of Adelaide, are working collaboratively with Dr Camilleri to fine-tune and adapt Yalumba’s LCA to meet the needs of the project. Dr Ira Pant (Tarac Technologies) and Dr Juanita Day (Amcor Australasia) are assisting with both the value chain analysis and the life cycle analysis. General project management is under the stewardship of Dr Cecil Camilleri.

Australian Greenhouse Office (2006). Greenhouse Friendly Guidelines, [Online], Department of Climate Change. Available from: <http://www.climatechange.gov.au/greenhousefriendly/publications/gf-guidelines.html> [01 June 2008].

Australian National Dictionary Centre (2007). Meanings and Origins of Australian Words and Idioms, [Online], Australian National University. Available from: <http://www.anu.edu.au/andc/index.php> [14 May 2008].

Australian Wine and Brandy Corporation (2008). Winefacts Statistics: Full range of export approval data - by source region, [Online], Australian Wine and Brandy Corporation. Available from: < https://www.awbc.com.au/winefacts/data/default.asp> [26 May 2008].

Baier, Annette (1986). Trust and Antitrust. Ethics, 96 (January), 231-260.

Beeston, J. (1994). A Concise History of Australian Wine. Allen and Unwin: Australia

Bonney, L, Clark, R., Collins, R. and Fearne, A. (2007). From Serendipity to Sustainable Competitive Advantage: Insights from Houston’s Farm and Their Journey of Co-Innovation. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 12 (6), 395-399.

Brundtland Commission (1987) (World Commission on Environment and Development). Our Common Future. Oxford University Press: New York.

Camilleri, C.S. (1998). Managing the Vineyard as a Micro-Cultural Landscape – A Gestalt Experiment in Landscape Ecology. In R.J. Blair, A.N. Sas, P.F. Hayes and P.B. Hoj (Eds), 2025 – Meeting the Technical Challenge. Conference Proceedings of the Tenth Australian Wine Industry Technical Conference: Sydney, Australia.

Camilleri, C.S. (2000). Environment Improvement Programme. The Yalumba Wine Company: Angaston, South Australia.

Camilleri, C.S. (2003). Towards a Sustainable Development Paradigm for the Australian Wine Industry – Case Study, The Yalumba Wine Company. Doctoral Thesis. Charles Sturt University: Wagga Wagga.

Camilleri, C.S. (2004). The Purchase of Wine as an Ecologically Responsible Activity. The Yalumba Wine Company: Angaston, South Australia.

Camilleri, C.S. (2008a). Sharing Yalumba – Communicating Yalumba’s Commitment to Sustainable Winemaking. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 13 (1), 18-41.

Camilleri, C.S. (2008b). The Ecological Modernisation of The Yalumba Wine Company. Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Technology. Deakin University: Victoria.

Camilleri, C.S. (2008c). Sustainable Value Chain Analysis – A Case Study of South Australian Wine. A Project of the Residency of Prof Andrew Fearne. Adelaide Thinker in Residence, Department of Premier and Cabinet: Adelaide, South Australia.

Camilleri, C.S., Birckhead, J. Bauer, J. and Freeman, B. (2000). Developing Social and Biological Indicators of A Sustainable Viticultural Landscape – Case Study the Limestone Coast Viticultural Zone in the South-East of South Australia. Part One: In J.L. Craig, N. Mitchell and D.A. Saunders (Eds.), Fundamental Concepts and Methodologies. In Conservation in Production Environments – Managing the Matrix. Surrey Beatty and Sons: N.S.W., Australia.

Carbon Trust (2008). PAS 2050 - Measuring the embodied greenhouse gas emissions in products and services, [Online], Carbon Trust. Available from: <http://www.carbontrust.co.uk/carbon/briefing/developing_the_standard.htm> [01 June 2008].

Edelman, R. (2003). The Relationship Imperative. IMC Journal of Integrated Communications, 2-13.

Fearne, A. (2008). Value Chain Analysis – Methodology Guide. Centre for Supply Chain Management, Kent Business School, University of Kent: Canterbury, U.K.

Forsyth, K., Oemcke, D. and Michael, P. (2008). Greenhouse Accounting Protocol for the International Wine Industry. Version 1.1, [Online], Winemakers’ Federation of Australia. Available from: <http://www.wfa.org.au/environment.htm> [30 May 2008].

Global Commerce Initiative, Capgemini, Intel (200). 2016 – The Future Value Chain, [Online], Global Commerce Initiative. Available from: <http://www.gci-net.org/> [27 May 2008].

Government of S.A. (2007a). South Australia’s Strategic Plan, [Online], Government of South Australia. Available from: < http://www.saplan.org.au/> [20 May 2008].

Government of S.A. (2007b). Climate Change and Greenhouse Emissions Reduction Act 2007, [Online], South Australian Legislation, Attorney General’s Office. Available from: <http://www.legislation.sa.gov.au/index.aspx> [23 May 2008].

Grayson, K. and Martinec, R. (2004). Consumer Perceptions of Iconicity and Indexicality and Their influence on Assessments of Authentic Market Offerings. Journal of Consumer Research, 31, 296-312.

Grunig, J.E. (2002). Qualitative Methods for Assessing Relationships Between Organizations and Publics, [Online], The Institute for Public Relations. Available from: <http://www.instituteforpr.org/> [26 April 2008].

Gustafsson, C. (2006). Brand Trust and Authenticity - The Link between Trust in Brands and the Consumer’s Role on the Market. Euriopean Advances in Consumer Research, 7, 522-527.

Hill Smith, R. (2007a). Share Yalumba. Share the Future. Y-Info Brochure. The Yalumba Wine Company: Australia.

Hill Smith, R. (2007b). Quoted in A. Buckingam, Independence Shines Through, Shanghai Daily, Thursday, 22nd March, 2007.

Hlupic, V. and Qureshi, S. (2003). What Causes Value to Be Created When It Did Not Exist Before? A Research Model for Value Creation. Proceedings of the 36th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 1-10.

Holt, D.B. (2002). Why do Brands cause Trouble? A Dialectical Theory of Consumer Culture and Branding. Journal of Consumer Research, 29 (June), 70-90.

Hon, L.C. and Grunig, J.E. (1999). Guidelines for Measuring Relationships in Public Relations, [Online], The Institute for Public Relations. Available from: < http://www.instituteforpr.org/> [26 April 2008].

Johnson, H. (1992). The Story of Wine. Mandarin: U.K.

Leahy, T. (2007). Tesco, Carbon and the Consumer, [Online], Tesco. Available from: <http://www.tesco.com/> [26 May 2008].

Linn, R. (1999). Earth, Vine, Grape, Wine - Yalumba and its People. Samuel Smith & Son: Adelaide

McCrindle, M. and Beard, M. (2007). Seriously Cool – Marketing, Communicating and Engaging with the Diverse Generations, [Online], McCrindle Research. Available from: <www.mccrindle.com.au> [27 April 2008].

Paine, K.D. (2003). Guidelines for Measuring Trust in Organizations, [Online], The Institute for Public Relations. Available from: < http://www.instituteforpr.org/> [26 April 2008].

Porter, M. (2004 [1985]). Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance. Free Press: New York

Remmen, A., Jensen, A.A. and Frydendal, J. (2007). Life Cycle Management – A Business Guide to Sustainability. UNEP Division of Technology, Industry and Economics: Paris.

Taylor, D.H. (2005) Supply Chain Analysis: An Approach to Value Chain Improvement in Agri-Food Chains. The International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management, 35 (10), 744-761.

Womack, J.P., Jones, D.T. and Roos, D. (1990). The Machine That Changed the World : The Story of Lean Production. Rawson and Associates: New York.

End Notes