|

|

|||

Department of Agriculture and Food Systems

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

|||

Department of Agriculture and Food Systems

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

Agribusiness Perspectives Papers 2000Paper 38 The Northern Myth revisited

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| North of the Tropic of Capricorn (Avg. 1993-97) | South of the Tropic of Capricorn (Avg. 1993-97) | East Kimberley (Avg. 1996-98) | |||

| Irrigated (Burdekin1) | Non-irrigated (Hurbert1) | Irrigated (n.a.) | Non-irrigated (Hurbert1) | Irrigated (ORIA2) | |

| Area Planted (ha) | 59,545 | 50,458 | - | 66,245 | 3,018 |

| Cane Production (t) | 7,230,853 | 4,638,807 | - | 5,643,982 | 425,033 |

| Sugar produced (t) | 1,071,612 | 628,558 | - | 789,593 | 44,203 |

| Cane yield (t/ha) | 121.4 | 91.9 | - | 85.2 | 104.8 |

| CCS levels (%) | 14.82 | 13.55 | - | 13.99 | 10.40 |

| Sugar yield (t/ha) | 18.00 | 12.46 | - | 11.92 | 14.65 |

| Cane:Sugar ratio | 6.75 : 1 | 7.38: 1 | - | 7.15 : 1 | 9.62 : 1 |

1) Burdekin district is covered by four mills: Invicta, Pioneer, Kalamia, and Inkerman. Herbert district is covered by two mills: Victoria and Macknade. Southern district is covered by seven mills: Fairymead, Millaquin, Bingera, Isis, Maryborough,

Moreton and Rocky Point.

2) from Leslie and Byth (1998)

Figure 4: Development of world sugar price over period 1993-1996 (source: DowJones)

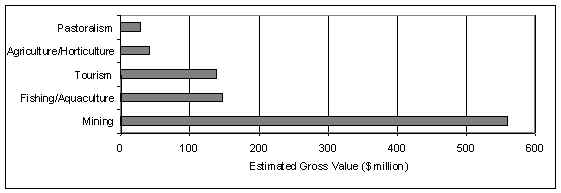

Agriculture is only one of a number of natural resource-based industries in the Kimberley. Figure 5 shows that mining (diamonds, gold, iron ore, lead/zinc. oil etc) is the highest revenue earner. Pearling along the West Kimberley contributes the lion's share to the region's revenue from aquaculture and commercial fishing but the Bonaparte Gulf, Ord River and Lake Argyle are important sources of fish and prawns. Pastoralism is the oldest industry in the region. It is based on cattle production across the vast Kimberley rangelands.

Figure 5: Estimated Gross Value of Kimberley Primary Industries 1995

(source: Kimberley Development and Transport Commission 1997)

In 1995, tourism was the third largest natural resource-based industry. The Kimberley has become a major Australian and world tourist destination. In 1996/7 there were approximately 260,000 visitors to the region (ABS 1998). Average annual tourism growth over the previous five years was 5.6 per cent.

Together, nature-based industries account for about 43 per cent of gross domestic product generated in the Kimberley (Department of Commerce and Trade 1996). The regional economy is also highly dependent on public administration, community services and construction.

Agriculture and Fisheries employ about 7.26 per cent of the workforce. Health and community services is the region's largest employer making up 27.3 per cent of the total Kimberley work force. More than half of the Aboriginal work force is employed in this sector (ABS 1998; Kimberley Land Council 1995). In all other sectors Aboriginal people make up a small proportion of the work force.

The Kimberley population is estimated at about 28,000 of which just over 10,000 live in the two easterly local government areas (Wyndham-East Kimberley and Halls Creek) which cover most of the Ord River catchment (ABS 1998). Mean annual population growth in these shires between 1991 and 1998 was 2.6 per cent. Approximately half the population is Aboriginal.

The Kimberley Economic Development Strategy (Kimberley Development Corporation 1997) encapsulates the vision for future development of the region: "To achieve a dynamic and diverse economy characterised by sustainable and balanced economic and social growth generating an enhanced and prosperous quality of life for all its people" (p.xi). It stipulates that "Maintenance of the region's unique lifestyle, increased Aboriginal participation in the mainstream economy and management of the sensitive environment are key challenges the region will face in years to come" (p.ix). The strategy reflects a strong belief that the nature-based industries will be central to the achievement of this vision. Ord Stage 2 and tourism growth are mentioned as key components of the development strategy (p.xiii).

The regional strategy sees economic growth as the key to development. It does acknowledge, however, that development is not solely about increased GDP but also about social and environmental improvements. This thinking is in line with the concept of ‘sustainable development' (World Commission on Environment and Development 1987: p.43) which acknowledges that increasing quality of life equally embodies satisfaction of non-material human needs and fulfilment of desires and aspirations many of which are directly related to environmental quality.

In his discourse on sustainable development, Gallopín (1996) stresses that more emphasis should be placed on services and technologies rather than resource-dependent industries as carriers of economic growth. He employs a Venn diagram to conceptualise that development, measured as increased quality of life, can occur in the absence of material economic growth and that economic growth does not guarantee ‘development' as quality of life can be declining specifically if growth is material dependent (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Venn diagram representing quality of life, material economic growth and non-material economic growth (source: Gallopin 1996)

Sustainable regional development is increasingly becoming synonymous with community governance as there is a trend of transferring responsibilities from federal and state governments to the regional level (Gates 1999).

Under a new ‘partnership framework' envisaged for Australia, local government holds the key legislative obligation to adopt policies and engage in activities that are consistent with State and national policies and regional plans for natural resource management (National Natural Resource Management Task Force 1999). The thinking is that "the devolution of decision making will enable regional communities to determine the mixture of mechanisms [..] that is most appropriate in their region" (p.39). This reflects the idea that regional communities have a ‘duty of care' whereby community and industry groups, landholders, philanthropists and government are stakeholders in the design and implementation of regional strategies (p.45).

Focussing on sustainability at the local and regional level makes sense for a number of reasons. It is the level where changes are seen and felt in an immediate manner. It is the level where consequences of environmental degradation are most acutely felt and where successful intervention is most noticeable (Bridger and Luloff 1999).

A series of federal and State policies and legislation in Australia already encourage regional involvement and governance. Examples are the initiation of catchment management bodies by the States to pursue and implement integrated catchment management in the early 1990s (Johnson et al. 1996) and more recently, an ecosystem-based and consultative process of implementing the federal Oceans Policy. At the local level, new forms of citizen participation in planning are emerging, not only in Australia (Plein et al. 1998).

Regional governance requires a high level of community participation in planning and decision-making processes. The success of regional governance therefore hinges critically on the capacity of stakeholders to engage meaningfully in these processes. Capacity development and social mobilisation are critical steps in empowering regional communities to play the significant role that they have been assigned in regional sustainable development. Research is critical in supporting regional governance.

A shift in the concept and understanding of research and development activities is required to support the paradigm shift at the policy level. The traditional linear research-extension-adoption model whereby people and decision makers were supposed to act rationally - in the sense that they implemented what researchers told them was ‘best' for them – has been abandoned. In its place a philosophy has emerged of facilitating change and sustainable development by engaging stakeholders, embracing their knowledge and ways of thinking and empowering participants in decision making through a processes of co-learning, negotiation and co-management.

The first part of this section (4.1) introduces the Ord-Bonaparte Program (OBP). The program represents a multi-agency interdisciplinary R&D program whose objective it is to support regional governance in the East Kimberley. Section 4.2 outlines the role of ecological economics analysis for sustainable development and highlights some key aspects of theoretical thinking. On this background, section 4.3 details the main ideas for an economics research contribution to the OBP.

The framework for a large research program has been established for the East Kimberley region. The recently completed business plan outlines the scope of research to be undertaken in the East Kimberley over a 5-year project commencing in July 2000 (CSIRO 1999). The objective of Ord-Bonaparte Program is to empower the people and institutions in this large, sparsely populated, natural resource rich region to manage their natural resources into the future in a manner that generates economic wealth, addresses issues of inter- and intra-generational equity and guarantees ecological sustainability.

The concept of the OBP is grounded in a scoping study into sustainable development of tropical Australia (Johnson et al. 1996). This study highlightes the need for research to integrate technical, institutional and capacity development aspects to address the full range of current limitations to sustainable development. The ultimate aim is the removal of those impediments and support the implementation of regional governance.

The OBP seizes the opportunity to "assist the community to plan and achieve sustainable futures" (CSIRO 1999:p.1). It does so by bringing together existing and new research activities into natural resource management by a series of local, State and national organisations and agencies. The program pursues two avenues. The more traditional avenue is to generate ecological, bio-physical, economic and social data and knowledge and to provide a scientific understanding of regional development as a complex adaptive system. The second avenue is to implement processes of learning and participatory action research that can underpin engagement, negotiation, planning processes and sustainable development in the region in the long term.

Key issues in the East Kimberley region include irrigation, aquaculture, tourism development and the integration of Aboriginal stakeholders and the community at large in planning processes and adjustments of institutional structures to facilitate regional governance (Johnson et al. 1996). The diversity and importance of these issues highlight the complexity and difficulty of tasks surrounding sustainable regional development.

Sustainable regional development can be conceptualised as a complex system. A ‘systems approach' is needed to track the web real-world problems and issues involved. Systems analysis is a way of conceptualising and analysing the complexity of sustainable regional development by looking at the entirety of a problem in its specific context with all its ‘hard' scientific and ‘soft' social dimensions. The major analytical objective of systems analysis is to enable the comparison of alternative options in the light of their possible outcomes (Checkland 1981).

The systems approach is reflected in the OBP structure (CSIRO 1999). The program is made up of five ‘objectives' which reflect areas of research centred around key natural resources and their management. They are ‘sustainable rangeland systems', ‘integrated water resource planning and management' and ‘sustainable coastal and marine systems'. ‘Aboriginal natural resource planning and management' deals specifically with indigenous issues of natural resource management. ‘Regional resource futures' develops methods and tools for integrated regional analysis and program evaluation in an effort to pull the research together in an interpretive and participatory manner. Each objective is further disaggregated into ‘strategies' which outline the specific research needs.

Cutting across the five objectives are nine research ‘themes' which provide methodological foci and channel stakeholder interest. The themes are ‘biophysical resource inventory', ‘process understanding', ‘socio-economic data and understanding', ‘synthesis and integration', ‘participation', ‘institutions', ‘capacity', ‘indigenous social and cultural issues' and ‘monitoring and evaluation'.

As the OBP approaches sustainable natural resource management as a systems issue, the natural basic reference area is the catchment. The Ord River catchment area is approximately 100 times greater than the anticipated total ORIA of approximately 80,000 hectares or 800 square kilometres.

The hydrological catchment boundaries, however, are not congruent with what can be called the limits of the ‘social catchment' relevant to the study, characterised by administrative boundaries and the social, cultural and economic activities and linkages of the people living in this region. The area of the social catchment is about three times the size of the actual Ord River catchment, extending approximately 300 kilometres east-west and 750 kilometres north-south, and covering some 250,000 square kilometres of land.

A large proportion of land is now under Aboriginal control or ownership and more is subject to Native Title claims, future lease take-overs and land acquisitions. This alone makes Aboriginal people a key stakeholder in natural resource management. When Ord Stage 1 was developed, Aboriginal values and interests were completely ignored (Coombs 1989). Head (1999) argues that three conceptualisations were responsible for this. The landscape was deemed ‘empty' and uninhabited wilderness. Aboriginal people were ‘invisible'. Agricultural land use was idealised and the thought of water running down a river without being unutilised was perceived as ‘waste'. Consultation and negotiations with Aboriginal groups are happening for Ord Stage 2 but proceedings and details are confidential.

Aboriginal people represent about half the population in the Kimberley region and represent a major economic force in the regional economy. A study by Crough and Christopherson (1993) showed that if the value of production of the Argyle diamond mine was excluded from estimates of the regional economy, then spending attributable to Aboriginal people in the Kimberley region represented approximately 40 per cent of the income of the Kimberley regional economy in 1991/92 (p.265).

The OBP acknowledges that increasing communication and information exchange between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal segments of the community are paramount for long-term planning and management. The program places specific emphasis on Aboriginal involvement in an effort to provide a much better understanding of Aboriginal land-use systems, values and aspirations. Aboriginal people have had a close association with the country for at least 18,000 years (Dortch 1977). Traditionally, Aboriginal people apply multiple uses to enhance their chances of providing a livelihood and to increase sustainability of the land as a whole. The OBP seeks to specifically build capacity among Aboriginal people so that they can participate more actively in regional natural resource planning and management.

Subsequently, the paper outlines the opportunities that resource, environmental and ecological economic approaches provide to address not only individual natural resource management matters but also the issue of sustainable regional development at large.

In the past, much of the debate about (agricultural) development – not only in the East Kimberley - was dominated by efficiency arguments. Benefit-cost analysis was employed to quantify returns on public and private investment and gross-margin analysis determined annual selection of crops. This thinking, of course, is much too narrow to support arguments about ecologically sustainable development including human welfare and equity.

Sustainable regional development, as mentioned above, can be conceptualised as a complex system. Systems are groups of interacting, interdependent parts linked together by exchanges of energy, matter and information. Complex systems are characterised by strong interactions between the parts, complex feedback loops that make it difficult to distinguish cause from effect, and significant time and space lags, discontinuities, thresholds, and limits (Costanza et al. 1993). Analytical frameworks tend to become more complex as their scope is increased (ie. more issues are included into the analysis). Increasing scale, (ie. the geographical and temporal boundaries) can have the same effect. Scale and scope are key criteria in modelling complex systems along with generality, realism, precision and resolution. Importantly, these features are interrelated.

Ecological economics provides a suitable conceptual and analytical framework for investigation the issue of sustainable regional development as it explicitly attempts the integration of multiple disciplines. Ecological economics can be seen as the "study of compatibility between human economy and the environment in the long-run" (Martinez-Alier and O'Conner 1996:p.154). This acknowledgment of interdependence between economic and natural systems is the core defining feature of ecological economics Common (1996).

The OBP can be seen as an ecological economic research approach as it pursues, in an applied sense, the goal of ecological economics to "enhance the capacity of the community to develop a ‘shared vision' as the prerequisite to generating momentum, supported by policies, to move toward ecologically sustainable development" (Meadows 1996:p.117). Ecological economics can contribute not only to the conceptualisation and analytical stages of the OBP. It also needs to play a critical role in the implementation of the research by assisting the regional stakeholders to translate the outputs of scientific inquiry into political action (Leff 1996:p.78).

The inquiry into sustainable development requires a ‘trans-disciplinary framework' According to Costanza et al. (1996:p.1) this framework must integrate three core elements:

Four notions are seen as fundamental to an ecological economics approach (p.2):

Quantitative analysis plays a key role in generating the knowledge and understanding required to underpinning this process. The models applied need to fulfil three core conditions (Constanza et al. 1996:p.7). They must:

O'Conner et al. (1996) are concerned with the ‘plurality of legitimate perspectives'. "Any natural system that is of interest to use has properties that affect our welfare. Our scientific priorities as well as our descriptions of these systems and their relation will reflect our interest, our ethical preoccupations, and our passions" (p.228).

Institutional and cultural variety and alternative assumptions about social preferences and environmental dangers must be accounted for in an analysis. This can be achieved, for example, by comparative scenario simulations and sensitivity testing. Even so, there are limitations to the validity of the analysis. O'Conner et al. stress that "in the view of emergent complexity the spectrum of future environmental effects unfolding over space and time is not specifiable in advance, and a probability distribution cannot meaningfully be identified" (p.229). They design a typology of uncertainty according to two criteria (Figure 7). The first relates to the supposed probability distribution of events and the second to the reliability or confidence placed in probabilistic knowledge propositions.

Figure 7: Classification of (un)certainty (adapted from O'Conner et al 1996)

Martinez-Alier and O'Conner (1996) regard questions on ‘ecological distribution' as a key aspect of ecological economics (p.161). What is the distribution of benefits of present patterns of natural resource use and environmental management? Which social groups carry the principal burdens of unwanted side-effects, for example from the loss of environmental amenities resulting from environmental degradation? How are they distributed across societies, space, and time? How are these asymmetries valued?

Ekins (1996) sees economists' tasks shifting away from a normative role of defining goals to a role of advising "on ways of minimising the costs of achieving [sustainability] within an institutional framework that recognises the pervasive and profound, if uncertain, links between ecosystems and the socio-economy, and the dangers of attempts at partial maximisation or optimisation in such a context" (p.147).

Tainter (1996) stresses the importance of embracing historical knowledge. "Historical knowledge is essential to sustainability. [..] Rarely will the experience of a lifetime disclose fully the origin of an event or a process. [..] No program to enhance sustainability can be considered practical if it does not incorporate such fundamental knowledge" (p.61). Gupta (1996) points out the specific importance of indigenous and local ecological knowledge systems. "Indigenous visions of how the world works will be essential in generating the technological and institutional innovations for sustainability" (p.92).

There are a wide variety of qualitative and quantitative economic methods that can meaningfully contribute to a better vision for sustainable regional development, improved understanding of the underlying regional processes, a sound grasp of the options for development and their consequences, and a comprehension of the policies that can be employed to achieve the vision.

Traditional resource and environmental economics approaches have been criticised for being narrow and focussed. Ekins (1996) argues that commonly applied modelling and econometric techniques are limited in their usefulness by strict assumptions, including perfect knowledge and competitive market and by non-inclusion of unpriced environmental effects and socio-cultural matters. He argues that optimal resource allocation and extraction trajectories derived from such analysis therefore run the risk of defining ecological un-sustainability.

This criticism is certainly valid in the broader sense, but traditional methods such as input-output analysis, benefit-cost and gross margin analysis, and mathematical programming models at farm and regional scale will always contribute valuable insights into aspects of what is a complex regional system (Van Kooten 1993). The challenge is bring various techniques together and provide an interpretation of the results within a consistent ecological economics framework. With this in mind, the paper goes on to suggest different methods of economic analysis – without claiming to be inclusive – towards an integrated economics research framework for the OBP.

Input-output analysis is an important tool in assessing an industry's contribution to a region. It can trace the resources and products within the regional economy and show, for example, the interdependence between various sectors of the economy or the effects of government spending (Midmore 1991). It can identify monetary and employment multipliers as well as leakage out of the regional economy (Robinson 1997, Hubbard and Brown 1979). Mining, for example, is the single largest industry in the East Kimberley in terms of revenue generated. However, its contribution to the region through employment and monetary multiplier would be rather small due to the structure of the industry. Mining operations tend to fly in/out staff from capital cities and house them in purpose-built settlements. As far as the region is concerned, they ‘import' inputs and ‘export' outputs. Input-output analysis can quantify the true monetary and employment multiplier effects of different (natural resource based) industries and thereby assist the process of prioritising alternative directions of development for the regional community.

Modified forms of input-output analysis and combinations with dynamic systems models and scenario analysis have been applied to make explicit the link between the level of economic activity and corresponding ‘ecological footprint' or impact on the environment (Bicknell et al. 1998; Schembri 1999).

The question of whether Ord Stage 2 will go ahead - assuming approval of the development proposal by WA and NT environment protection agencies and successful negotiations with indigenous stakeholder - is a commercial decision and will not be influenced by the OBP. Most likely, a decision will be taken before the OBP commences in July 2000. However, the development will have significant environmental implications, which the OBP has a role in evaluating.

Ord Stage 2 would be the largest consumer of irrigation water, which, as a consequence, is poised to become a scarce resource. Mathematical programming techniques can be employed to show optimal spatial and temporal water allocations, quantify water-use efficiency and quantify trade-offs between different users of water, different irrigation areas, different crops and different irrigation techniques. By introducing stochastic elements into the analysis, the implications of climatic risk can be examined. These results can inform the process of allocating water entitlements between different user groups and users. Scarcity of water will force the introduction of a consumption-based price for water that can be determined through marginal cost analysis. In combination with farm-scale modelling ‘best practice' can be supported beyond current understanding (Kimberley Development Commission 1998).

More trade-offs at the catchment level warrant investigation. Issues of efficient and ‘optimal' use of land and water resources and treatment of externalities are best investigated at this scale and numerous economic studies have taken a catchment approach (eg. Greiner 1997). Irrigation occurs on a relatively small area within the Ord River valley but it affects the entire catchment. Water supply is reliant on the runoff generated in the upper catchment which is predominantly grazed. The impact of irrigation, through changed river flow, nutrient and sediment export, etc. is felt further downstream in the coastal and marine areas where recreational and commercial fishing are important industries. A catchment-scale understanding of the hydrologic system and its economic dimension is essential. An dynamic environmental-economic model covering the entire catchment area is required to provide an economic interpretation of the hydrologic system, the relationship between various natural-resource dependent industries and potential trade-offs between them.

There are a wide variety of modelling techniques available to deal with dynamic systems. Among them are simulation modelling, neural networks and agent-based modelling. Depending on the purpose of the individual modelling exercise, specific techniques might be favourable (Costanza et al. 1996/2).

Non-market valuation will play a critical role for the economic research within the OBP. Non-market values are an important part of the total economic value of an ecosystem, specifically to indigenous people. Gatzweiler (1999) applied contingent valuation to elicit the value of ecosystem services attributed by indigenous people. He used the willingness-to-accept-compensation approach in the context of local indigenous ecological knowledge by embedding it into the specific institutional and value environment.

Other applications of non-market valuation methods can be envisaged in the field of tourism. Visitors may receive a substantial consumer rent from visiting the East Kimberley region. Tapping into the consumer surplus may provide opportunities for the region to better manage some areas and facilities. Also, new insights into visitor demands and expectations may generate the impetus for new tourist-related enterprises, specifically in the field of indigenous tourism.

Valuation techniques can be further employed to explore the relationships between different industries and resource users. To which degree are nature-based industries complementary? Are there resource conflicts? What is their nature and how large do people perceive them to be? Examples of questions are: Is there are complementary relationship between irrigation agriculture and tourism? What are the various aspects of that relationship? Is there a potential conflict between aquaculture development in Lake Argyle and residential water use in Kununurra?

All of the presented methods make a contribution to the community's ability to establish a vision for their region and define the regional objectives for sustainable development.

The second important aspect is examining how the vision might best be achieved with the help of policies and institutions (Lockwood 1999). Scenario analysis combined with dynamic modelling plays an essential role to that end. The effects of an exhaustive range of different policy instruments, in isolation and combination, need to be calculated and carefully assessed and interpreted. Combined with institutional analysis and design, this leads to a definition necessary structures and adaptive process. On this foundation, existing institutions and policies can be re-aligned and new ones developed to support long-term sustainable natural resource management.

In terms of providing the stakeholders with tools so that they can assess for themselves the relative merits and problems with alternative development scenarios and the potential array of outcomes, the focus must be on (1) transparency of input data and assumptions, (2) ease of use and (3) assistance in result interpretation and presentation. Within the second criterion it is important that the stakeholders are able to look at the system from their perspective. Perspectives differ between individuals and groups depending on their experience, purpose and weltanschauung. Different perceptions represent ‘mental models' or systems views which are relevant to the stakeholders concerned (Senge 1992; Ison et al. 1997). After all, the research will only be long-term relevant if the tools are appreciated as an essential means of learning about sustainable development and continuously used by stakeholders. Learning is the key towards successfully dealing with a rapidly changing human and natural environment and advancing from a re-active stance to one of developing pro-active natural resource management strategies within a framework of sustainable regional development.

The agricultural development of Tropical Australia has been a contentious issue and economic arguments have been at the centre of the political debate. This is exemplified in the case of the Ord River Irrigation Scheme in the East Kimberley. With the proposed expansion under Ord Stage 2 expected to go ahead shortly, it is shown that the proposal is isolated from a broader view of sustainable regional development. While agriculture plays an important role within the regional economy, it is but one natural-resource-based industry.

Ongoing devolution of federal and State responsibilities for natural resource management to regional communities on the one hand and a global shift in thinking towards sustainable regional development on the other hand create a unique opportunity for regional governance. This brings with it the onus on communities to develop the capacity to plan into the future and manage their resources in a manner that supports sustainable development.

It is argued that research and development play a crucial role in building capacity within the community and stakeholder groups so that they can substantially participate in the learning, visioning and policy setting processes that underpin regional governance. The Ord Bonaparte Program is an interdisciplinary multi-agency R&D initiative which will take place in the East Kimberley over the next 5-6 years.

The OBP is, in itself, an experiment in applied research and development for implementation of ecologically sustainable development at the regional level. It is shown that the philosophy behind the OBP is grounded in systems thinking and congruent with concepts emerging from the field of ecological economics. Socio-economic research will be a core component of the research program. The paper suggests a series of economic analytical techniques and methods that, in combination, will provide an essential contribution to developing strategies towards sustainable regional development.

Thanks are offered to Peter Byron for compiling much of the data presented.

Agriculture Western Australia (1999) Handbook for Horticultural Crops in the ORIA. Draft. Kununurra.

Agriculture Western Australia (1997) Ord River Irrigation Area. Kununurra.

Anon. (1995) The untapped irrigation potential of the Fitzroy Valley. Australian Cotton Grower 16(3): p30-31, 33-34.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (1998). Integrated Regional Database: IRDB98. ABS: Canberra.

Basinski, J. (1990) Comments on ‘The Ord River Irrigation Area – success in the Eighties'. Agricultural Science 3(1): 42.

Beech, D.F. (1975) Future prospects of irrigated agriculture in the Ord River Irrigation Area, N.A. pF1-F36 in, Symposium on irrigated agriculture in Northern Australia. North Queensland Sub-Branch, Australian Institute of Agricultural Science: Townsville.

Bicknell, K.B., Ball, R.J., Cullen, R., Bigsby, H.R. (1998) New methodology for the ecological footprint with an application to the New Zealand economy. Ecological Economics 27, 149-160.

Bridger, J.C. and Luloff, A.E. (1999) Toward an interactional approach to sustainable community development. Journal of Rural Studies 15, 377-387.

Bureau of Agricultural Economics (1964) The Ord River Irrigation Project: A benefit-cost analysis. Bureau of Agricultural Economics: Canberra.

Bureau of Agricultural Economics (1971) The Australian Cotton Growing Industry – and Economic Survey 1965-65 to 1966-67. AGPS: Canberra.

Checkland, P. (1981) Systems Thinking, Systems Practice. John Wiley & Sons: Chichester.

Common, M. (1996) What is Ecological Economics? P6-20 in, Gill, R. (ed) R&D Priorities for Ecological Economics. Occasional Paper 09/96. LWRRDC: Canberra.

Coombs, H.C. (ed) (1989) Land of promises. Centre for Resource & Environmental Studies and Aboriginal Studies Press: Canberra.

Costanza, R., Wainger, L., Folke, C and Maeler, K.G. (1993) Modelling complex ecological economic systems. BioScience 43, 545-555.

Costanza, R., Segura, O., and Martinez-Alier, J. (1996) Integrated envisioning, analysis, and implementation of a sustainable and desirable society. p1-16 in, Costanza, R., Segura, O., and Martinez-Alier, J. (eds) Getting down to Earth. Island Press: Washington DC.

Crough, G. and Christopherson, C. (1993) Aboriginal people in the economy of the Kimberley Region. Australian National University, North Australia Research Unit: Darwin.

CSIRO (1978) CSIRO's research in and for the Ord River Irrigation Area. CSIRO, Canberra.

CSIRO (1999) Ord-Bonaparte Program: R&D Plan 2000-2005. CSIRO Tropical Agriculture: Brisbane.

Davidson, B. (1972) The Northern Myth: Limits to Agricultural and Pastoral Development in Tropical Australia. 3rd ed. (fist published 1965). Melbourne University Press: Melbourne.

Department of Commerce and Trade (1996) WA 2029: Stage II: Development Options for Western Australia. Perth.

Department of Natural Resources (1976).

Department of Natural Resources (1976). An outline of the Ord Irrigation Project Western Australia. AGPS: Canberra. . AGPS: Canberra.An outline of the Ord Irrigation Project Western Australia. AGPS: Canberra.

Ekins, P. (1996) Towards an economics for environmental sustainability. p129-152 in, Costanza, R., Segura, O., and Martinez-Alier, J. (eds) Getting down to Earth. Island Press: Washington DC.

Gallopín, G.C. (1996) Technological intensity, technological quality, and sustainable development. p185-200 in, Costanza, R., Segura, O., and Martinez-Alier, J. (eds) Getting down to Earth. Island Press: Washington DC.

Gardiner, G. (1998) The Ord sugar industry – a greenfield project. p283-289 in, Outlook 98. ABARE: Canberra.

Gardiner, H.G. and Gardiner, M.A. (1999) Factors affecting yields of sugar on the Ord River. HG Gardiner & Associates: Kununurra.

Gates, C. (1999) Community governance. Futures 31, 519-525.

Gatzweiler, F.W. (1999) Contingent valuation of environmental functions – a participatory method to estimate the total value of rubber forest gardens in west Kalimantan. Quarterly Journal of International Agriculture 38, 128-139.

Gonzales, N.L. (ed) (1978) Social and Technological Management in Dry Lands. Westview Press: Boulder, Colorado.

Government of Western Australia and Government of the Northern Territory (1994) Ord River Irrigation Project. A review of its expansion potential. Perth.

Greiner, R. (1997) Integrated catchment management for dryland salinity control in the Liverpool Plains Catchment: a preliminary study from an economic perspective. Occasional Paper 12/97. LWRRDC: Canberra.

Gupta, A. (1996) Social and ethical dimensions of ecological economics. p91-116 in, Costanza, R., Segura, O., and Martinez-Alier, J. (eds) Getting down to Earth. Island Press: Washington DC.

Hannah, A.C. (1997) The world sugar market and reform. Cooperative Sugar 29, 251-265.

Head L. (1999) The Northern myth revisited? Aborigines, environment and agriculture in the Ord River Irrigation Scheme, stages one and two. Australian Geographer 30, 141-158.

Hubbard L.J. and Brown, W.A.N. (1979) The regional impacts of irrigation development in the Lower Waitaki. Research Report, Agricultural Economic Research Unit. Lincoln College: New Zealand.

Ison, R.L., Maiteny, P.T., Carr, S. (1997) Systems methodologies for sustainable natural resources research and development. Agricultural Systems 55, 257-272.

Johnson A.K.L, Shrubsole, D., and Merrin M. (1996) Integrated catchment management in northern Australia: from concept to implementation. Land Use Policy 13, 303-316.

Johnson, A.K.L., Cowell, S., Loneragan, N., Dews, G., and Poiner, I. (1999) Sustainable development of Tropical Australia: R&D for management of land, water and marine resources. Occasional Paper 05/99. LWRRDC: Canberra.

Kimberley Development Commission (1997) Kimberley Region W.A. Economic Development Strategy 1997-2010. Kimberley Development Commission: Kununurra.

Kimberley Development Commission (1998) Test Practice in Irrigated Agriculture. Kimberley Development Commission: Kununurra.

Kimberley Development Commission and the Dept of Transport (1997). Kimberley Transport Towards 2020: The Kimberley Region Transport Strategy. Kimberley Development Commission: Kununurra.

Kimberley Land Council (1995) Kimberley Aboriginal Labour Force: A preliminary survey of Aboriginal employment, education and training in the Kimberley region. Kununurra.

Leff, E. (1996) From ecological economics to productive ecology: perspectives on sustainable development from the South. P77-89 in, Costanza, R., Segura, O., and Martinez-Alier, J. (eds) Getting down to Earth. Island Press: Washington DC.

Leslie, J.K. and D.E. Byth (1998). An analysis of sugar production issues in the Ord River Irrigation Area: Preliminary Report. Report for the SRDC and the Ord Sugar Industry Board.

Lockwood, M. (1999) Environmental Economic R&D for Sustainable Natural Resource Management in Rural Australia: a Potential Role for LWRRDC. P42-63 in, Mobbs, C. and Dovers, S. (eds) Social, Economic, Legal, Policy and Institutional R&D for Natural Resource Management: Issues and Directions for LWRRDC. Occasional paper 01/99. LWRRDC: Canberra.

Mahony, N. and Wegener, M. (1999) Farm feasibility studies for sugarcane production in the Nebo and Blue Mountain districts of central Queensland. p280-286 in, Hogarth D.M. (ed) Proceedings of the 1999 Conference of the Australian Society of Sugar Cane Technologists, Townsville Australia, 27-30 April 1999. Editorial Services: Brisbane, Australia.

Martinez-Alier, J. and O'Conner, M. (1996) Ecological and economic distribution conflicts. p153-183 in, Costanza, R., Segura, O., and Martinez-Alier, J. (eds) Getting down to Earth. Island Press: Washington DC.

McGieh D. (1987) Agriculture in the Ord River irrigation area. Search 18, 179-182.

McGieh D. (1990) The Ord River irrigation area – success in the Eighties. Agricultural Science 3, 39-41.

Meadows, D. (1996) Envisioning a sustainable world. P117-152 in, , Costanza, R., Segura, O., and Martinez-Alier, J. (eds) Getting down to Earth. Island Press: Washington DC.

Midmore, P. (1991) Input-output in agriculture: a review. p5-20 in, Midmore P. (ed) Input-output models in the agricultural sector. Avebury: Aldershot, Hants (UK).

National Natural Resource Management Task Force (1999) Managing Natural Resource in Rurual Australia for a Sustainable Future. A discussion paper for developing a national policy. Draft. Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry--Australia: Canberra.

O'Conner M., Faucheux S., Froger, G., Funtowicz, S., and Munda, G. (1996) Emergent complexity and procedural rationality: post-normal science for sustainability. p223-248 in, Costanza, R., Segura, O., and Martinez-Alier, J. (eds) Getting down to Earth. Island Press: Washington DC.

Osman, M.A.E.K. (1998) An analytical study of world prices of sugar through 1980/1981 – 1995/1996 period. Assiut Journal of Agricultural Sciences 29, 195-210.

Patterson, R.A. (1965). The economic justification of the Ord River Irrigation Project. Australian and New Zealand Association for the Advancement of Science, 38th Conference, Hobart.

Plein, L.C., Green, K.E., Williams, D.G. (1998) Organic planning – a new approach to public participation in local governance. Social Science Journal 35, 509-523.

Robinson, M.H. (1997) Community input-output models for rural area analysis with an example from central Idaho. Annals of Regional Science 31, p.325-351.

Schembri, P. (1999) Adaptation costs for sustainable development and ecological transitions: a presentation of the structural model M3ED with reference to French energy-economy-carbon dioxide emission prospects. International Journal of Environment and Pollution 11, 542-564.

Senge, P.M. (1992) The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. Century Business: London.

Tainter, J.A. (1996) Complexity, problem solving and sustainable societies. p61-76 in, Costanza, R., Segura, O., and Martinez-Alier, J. (eds) Getting down to Earth. Island Press: Washington DC.

Transport and Kimberley Development Commission (1997) Kimberley transport towards 2020. Transport: Perth.

Van Kooten, G.C. (1993) Land resource economics and sustainable development: economic policies and the common good. University of British Columbia Press: Vancouver.

Walker K.J. (1973) The politics of national development: the case of the Ord River Scheme. Public Administration 32, 93-113.

World Commission on Environment and Development (1987) Our common future. Oxford University Press: New York

Young, N. (1979) Ord River Irrigation Area Review: 1978. AGPS: Canberra.

|

Contact the University : Disclaimer & Copyright : Privacy : Accessibility |

|

Date Created: 04 June 2005 |

The University of Melbourne ABN: 84 002 705 224 |