Agribusiness Review - Vol. 6 - 1998

Paper 9

ISSN 1442-6951

On Advancing Australian Trade, Investment and Commercial Opportunities in China:

Lessons from Wool Trade

Colin G. Brown, Senior Lecturer

School of Natural and Rural Systems Management

Hartley Teakle Building, The University of Queensland

Brisbane QLD 4072, Australia

Telephone: +61 7 33652148

Facsimile: +61 7 33659016

Email: Colin.Brown@mailbox.uq.edu.au

Abstract

Few markets offer so much yet pose such challenges to Australia's agricultural industries as does China. Australian industries, firms and trade negotiators have not coped well with the chaotic import and investment channels and with the policy gyrations. Drawing on the case of wool, so dominant in overall Sino-Australian trade and relations, the paper argues that only with a better understanding of Chinese problems and policies will the full potential of Sino-Australian trade be realised. As other key agricultural industries in Australia gear up on the Chinese market, they need to heed some of the hard-learnt lessons experienced by the wool industry.

Keywords: Sino-Australian trade, wool, policy intelligence

Introduction

Current concerns

Policies to be pursued

Identifying Common Interests

Promoting the Common Interest

Government and industry imperatives

References

The Prime-Ministerial visit to China in 1997 highlighted government and industry efforts to consolidate commercial links with China. Sino-Australian trade has risen dramatically over the last two decades as China has reformed its internal and external trade. But the trade has been extremely volatile with seemingly unforeseen events having dire consequences for Australian firms and industries. Furthermore, maintaining growth in the future will pose a greater challenge than past growth induced by the initial opening of the market.

The Prime-Ministerial delegation sought to confront these challenges and to consolidate commercial ties with China. This paper will argue, however, that while such high level representations and associated firm-to-firm contacts are necessary, they are in no way sufficient to maximise the potential of Sino-Australian trade and the investment and other commercial opportunities that arise. Such potential can only be realised when Australia has a better understanding of Chinese problems and policies.

Some ongoing concerns confronting Sino-Australian trade and commercial relations are first outlined. Australia and China share common interests in much of their trade, yet often it seems that China pursues policies or trade negotiations at odds with these interests. The central part of the paper describes how these common interests may be more complex and subtle than on first appearances. It also shows how being more aware of the way individuals are affected by growth in Sino-Australian trade can help identify means of promoting the common interests. Individual firms are unlikely to advance these interests, and the final section discusses the role of government and industry organisations in fostering them.

The dynamics of Sino-Australian trade have seen its perception as a lucrative and, at times, highly risky and opportunistic market. Many of the current firm and trade negotiation strategies are based on this overly simplistic perception. In turn, this has led to an Australian trade with China that has not coped well with the chaotic trade and import channels or with the boom and bust cycle associated with rapid Chinese growth and policy gyrations, and that has failed to take full advantage of the trade and commercial opportunities which have arisen.

Some of the concerns are clearly illustrated in the case of wool, Australia's major export to China (Commonwealth of Australia 1997) . Not only is wool important in value terms, but difficulties in negotiating wool import arrangements have dominated Sino-Australian trade negotiations. This paper draws heavily on the case of wool not only because of its importance in current Sino-Australian trade relations, but also because it is a harbinger of issues likely to arise for many commodities rapidly emerging in that trade. Chinese imports of Australian wool grew from around 20kt at the end of the 1970s to almost 200kt by the mid 1990s (Figure 1). In the process, China changed from being a relatively minor to Australia's major customer for wool accounting for over one-fifth of its total exports.

Much of wool imported from Australia has gone to export-oriented mills on the east coast and to township enterprise mills. The challenge for Sino-Australian wool trade is that expansion of the trade also relies on mills producing for the domestic market who have little experience in dealing with overseas traders or wool and who have less political support to import that wool. Figure 1 reveals not only an increasing trend in wool imports but also significant volatility. The collapse in Chinese wool imports from Australia in the late 1980s affected seriously Australia's foremost rural industry and left a legacy of industry restructuring that lingers into the second half of the 1990s (Brown and Longworth 1995) .

Although wool has attracted most attention, it is by no means alone. Other commodities such as sugar, various grains, and cotton have seen similar growth in Sino-Australian trade, and a similar volatility. The short-term impacts of the volatility for these industries has yet to match the dramatic events that plagued the wool industry. Nevertheless, it has led to major revisions of marketing plans. In the medium-term, the volatility has led to the extremes of either an extremely bullish approach where normal market intelligence and risk management are ignored or an overly cautious approach where many market opportunities are missed.

Figure 1

Rarely is there a systematic attempt to comprehend and monitor the volatility and to develop appropriate strategies in response to it. Yet as argued elsewhere (Longworth and Brown 1995) , much of the volatility is hardly "unforeseeable" with clear systematic factors in operation, and that firms in the past have generally been unprepared and ill-informed.

The overly simplistic approach has extended to Sino-Australian trade negotiations. As mentioned, the negotiations have come to a standstill over seemingly irreconcilable differences on wool import arrangements. As part of its attempted accession to the World Trade Organisation (WTO), China is proposing a new quota/tariff regime on wool imports, with higher rates of tariff on above quota levels of import. Australia has been reluctant to conclude a trade deal which will see more formal import quotas imposed on its wool exports, and has been seeking either no trade restrictions or, at worst, a system of tariffs

Despite some positive rhetoric in 1997, wool trade negotiations have again seemingly stalled. A new approach is needed to advance the wool trade negotiations and with it, overall Sino-Australian trade negotiations.

In order to identify ways of advancing Sino-Australian trade, it is first necessary to be aware of the broad policy interests of both Australia and China in a particular commodity trade. In the case of wool, the policy implications are closely intertwined as China and Australia dominate world markets for wool and wool textile products. Thus, policies pursued by either country will impact on the other, and it is in the interests of both countries to revisit the vexed question of wool trade arrangements. Reforming wool trade arrangements and improving relations will enhance the role of China in global wool textile production and, at the same time, is central to the fortunes of Australia's premier rural industry.

The policies the Australian wool industry and the Australian government should pursue in relation to China and wool have been argued at length in response to the crisis that has gripped the Australian wool industry since the late 1980s. The report of the Wool Industry Review Committee (Garnaut et al . 1993 ) set out a series of recommendations which formed the basis of major industry restructuring. The report and subsequent industry restructuring generated considerable debate (see, for example, Chisholm et al . 1994) . Longworth and Brown (1995) and Brown and Longworth (1994) provided detailed analysis of specific policy measures for the Chinese wool market. Despite the differing opinions, there is a consensus that Australia should promote measures designed to facilitate import flows, to improve import channels, to improve the technical capabilities of Chinese mills, and to make these mills more aware of Australian wool.

This differs from other commodities in Sino-Australian trade where Australia has a relatively small share of world trade and where its policy actions are largely independent, with few feedback effects on the Chinese market.

The Australian wool industry needs China. Shifting comparative advantage in world textile production to China consolidates its role as the major customer of Australian wool. The policies and strategies employed by Australia need to ensure a smooth transition from some of its more traditional East-Asian markets to the Chinese market. More importantly, China represents a genuine "new" market for Australian wool in terms of an expected increase in domestic per capita consumption of wool in China. The wool industry is desperately seeking new markets to reduce the wool stockpile and to bring it out of the low prices that have beset it during the 1990s.

If the Australian wool industry needs China, then China also needs Australian wool. The quality of Chinese wool falls well short of Australian wool being shorter, less sound, more heterogeneous and having lower clean yields (Longworth and Brown 1995: 150-151) . Many of the quality problems relate to the harsh physical conditions in China's pastoral region and have no simple technical or managerial solution. Even if Chinese wool did approach the quality of Australian wool, the badly degraded state of China's rangeland imposes a major limit on sheep numbers and greasy wool output in China (Longworth and Williamson 1993) . Thus domestic Chinese wool produces neither the quantity or quality needed to service its rapidly expanding wool textile industry, and so access to Australian wool is essential.

For socio-political and strategic reasons, Chinese authorities view an integrated wool industry as important in the development of the remote and industrially-backward, pastoral regions. However, the poor quality of domestic wool creates enormous problems for "up-country" Chinese mills located in the main wool growing areas. Many Chinese mills now importing Australian wool also use domestic wool. The long-term viability of these mills depends on their access to better quality imported wool (Brown and Longworth 1994) . Conversely, from an Australian perspective, improving the quality of domestic wool and its marketing channels is central to improving the viability of these mills and their ability to pay for imports of Australian wool.

On the trade policy arena, China needs to pursue its participation in trade organisations such as the World Trade Organisation for its key textile industry. One of the main outcomes from the Uruguay round was reform of the Multi-Fibre Arrangement, an arrangement that has severely distorted trade flows in world textiles, under the Agreement on Textiles and Clothing. The timetable for reform under the Agreement on Textiles and Clothing means that most of the benefits for textile producers are yet to emerge. However, as the bulk of the reforms begin to impact over the next five years then the potential benefits and incentive for China to be part of this Agreement will escalate.

Given China's dominance in world clothing trade, its accession to the WTO is likely to impact on the Agreement on Textiles and Clothing possibly slowing implementation of the reforms.

The strong complementarity between the Australian and Chinese wool and wool textile industries mirrors similar relationships for most of the commodities traded between the two countries. Indeed, the complementarity of the two economies is the cornerstone of the relationship between Australia and China. Yet despite the complementarity, in specific commodity markets, China often appears to take a stance which restrains these commercial links.

Although a growing Sino-Australian trade may be in the overall interests of both countries, various groups will be affected in different ways. Trade developments and policy measures create both gainers and losers. The losses may be perceived rather than real, and ephemeral in nature, yet they will still impact on the welfare of the adversely affected group. The distribution of gains and losses and the relative political strength of the affected groups influences the decision making process. Thus, understanding who gains and loses from a particular trade and in what way is critical. First, it helps design appropriate policies which enable a broader section of society to benefit from the increased trade. Second, it enables marketing and trade strategies to be developed which account for these different impacts, and which seek to relieve some of the adverse impacts while highlighting or enhancing the positive outcomes for the beneficiaries.

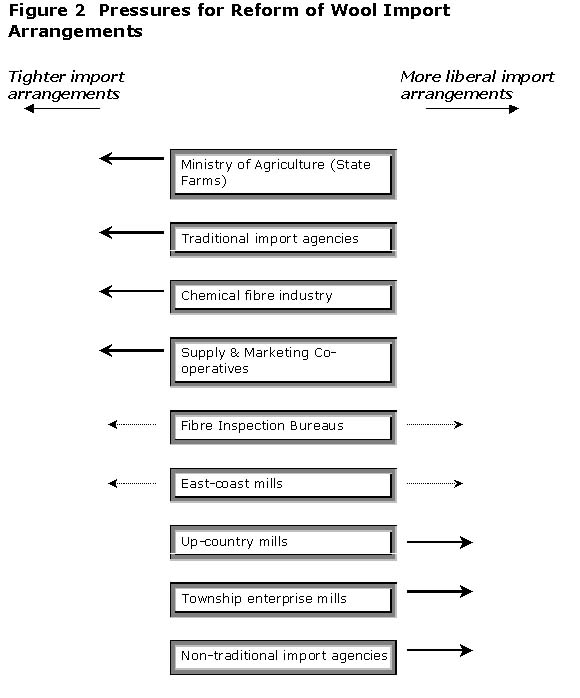

Understanding the different impacts, however, is not a trivial matter. In the case of wool, there are a plethora of groups each affected in different ways. The following discussion seeks only to highlight the complexity and subtlety of the effects using Figure 2 as a guide. A more comprehensive discussion of these impacts is provided elsewhere in Longworth and Brown (1995) .

The main push for more restrictive wool import arrangements has come from the Chinese Ministry of Agriculture notionally to protect local sheep herders. The Ministry of Agriculture has extensive extension, research and other infrastructure tied to the pastoral areas and any threat, perceived or otherwise, to the local wool industry would undermine that infrastructure. However, the Ministry of Agriculture also controls the wool-growing State farms which grow the best wool in China that may compete with imported wool under specific price relativities (see Longworth and Williamson 1993: 65-67) . It is these State farms, rather than the millions of individual herders, that the Ministry of Agriculture is seeking to protect with the import restrictions.

Figure 2

Note that Figure 2 is not a comprehensive list of groups affected by the wool import arrangements, but is a selective list of some of the key players. Other groups, such as clothing manufacturers, will also have a strong interest in the negotiations.

A range of other institutions relying on domestic wool have recently undergone major structural changes and may feel vulnerable to a surge in wool imports. For instance, since the deregulation of wool markets throughout China in 1992, the Supply and Marketing Cooperatives have lost almost half of their share of wool sales from their previous role as a sole procurement agency. As they are unlikely to be involved in the handling or distribution of imported wool, they may perceive imports as a further erosion of their wool supply base and so support tighter restrictions.

Opposition to greater wool imports is not confined to the local wool industry. The main beneficiary from China restricting wool imports in the late 1980s and early 1990s was not its domestic wool industry but instead its domestic chemical fibre industry (Lin 1993) . Indeed, one of the greatest threats to increased wool imports is the Chinese government's support for chemical fibre production. A full understanding of the political economy of Sino-Australian wool trade needs to extend beyond interests in the wool industry alone.

The primary support for a more liberal trade policy comes from the wool textile industry. As outlined in the previous section, Chinese mills need access to Australian wool. Although freer import arrangements, in general, favour all mills, some mills benefit more than others. Brown and Longworth (1994) categorise Chinese mills into three groups, namely the large State-owned mills on the east coast, township enterprise mills, and up-country mills. A tariff quota arrangement relative to more liberal import arrangements would favour the large State-owned mills on the east coast. These mills have well defined and traditional export markets and import channels, and have received preferential treatment when wool imports were restricted in the past.

Conversely, up-country mills, which have inferior equipment and information networks for wool textile exports and raw wool imports, are unlikely to receive their fair share of any restricted wool imports, especially when imports are restricted as a result of a fall in domestic demand and rise in domestic wool stocks. Township enterprise mills have the most to lose from more constrained import arrangements. Having emerged in the early 1980s, the township enterprise mills are more flexible in their labour and other arrangements compared with the State mills and now account for over 30% of China's wool processing capacity (Brown and Longworth 1994) . They are unlikely to be afforded special access to restricted imports as their imports come from outside the traditional channels. Not only would restricted wool imports impact on their profitability, but ongoing limits would force them to close or switch to other fibres.

Changes in import arrangements also affect the organisations involved with the trading and distribution of imported wool in China. Many different institutions are now involved in handling wool. These range from the traditional channels such as the Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Co-operation and its trading agencies such as CHINATEX, to the non-traditional channels such as intermediate wool trading corporations, secondary market traders and even individual mills (Longworth and Brown 1995: Section 11.2.2; IWS 1995) . Past changes in wool import arrangements have reflected power struggles among these groups as highlighted by the rapid rise and equally dramatic demise of the China Wool Group in the late 1980s.

The brief discussion above serves only to draw attention to the complex array of impacts that can arise from a change in Sino-Australian import arrangements. It also highlights the folly of adopting an overly simplistic approach to Sino-Australian trade and trade negotiations, and that identifying and promoting common interests is not a simple matter. The means by which China has sought to advance the trade in the face of a myriad of interests is outlined in the following section, as are the ways and issues involved in Australia fostering these common interests.

The Chinese government faces a dilemma. Its overall interests and those of particular groups are served by freer and increased access to Australian exports such as wool. Conversely, other influential groups feel threatened by a potential surge in imports. The Chinese government has addressed this type of dilemma in the past by creating a kind of trade policy "mirage". That is, notionally restrictive import arrangements are legislated while their implementation, administration and application allows a higher level of imports. Current Chinese proposals for a tariff quota regime appear to contain many of the elements of this mirage.

Thus even if China imposes a tariff quota import arrangement, it is unclear how it will administer it and whether it will restrict actual imports. The trade policy mirage seems a convenient means for serving the interests of China and Australia. But it comes at a cost. Restrictive quotas and tariffs have well documented distortionary effects and inefficiencies. Facilitating loopholes around these official restrictions can create additional problems such as greater uncertainty, encouraging abuse and distorting imported product flows and processing to where exemptions arise. Often the exemptions have unforeseen and unintended effects which may lead to even greater distortions than the original quotas and tariffs. More importantly, it encourages opportunistic merchants or traders rather than committed exporters and importers who require a much more certain policy environment to operate in. Thus elements of market development, information networks and a better matching of customer requirements with import supplies have been lacking in recent Sino-Australian trade.

Hence China's way of promoting the common interest has been to create this trade policy mirage. Conversely, Australia has pursued a singularly unsuccessful negotiating stance based on an ideal first-best policy of removing import restrictions. The question for Australian exporters and their Chinese customers is whether the trade policy mirage is a second best policy outcome relative to a binding tariff quota regime. In any event, Australian exporters operating in China and Australian trade negotiators need to fully understand the operation of this trade policy mirage.

The discussion in the previous section suggests there are ways around the trade impasse and ways of furthering the common interest that can avoid the distortion and uncertainty associated with the trade policy mirage. These strategies involve alleviating or minimising the concerns of those parties adversely affected by more liberal import arrangements while enhancing the gains to the beneficiaries. In the case of wool, the core of these efforts is Australian assistance to modernise and commercialise the domestic Chinese wool industry. The concerns of the Ministry of Agriculture may be allayed if assistance was provided to improve the quality and marketing of domestic wool in China to allow this wool to compete more effectively in the long run.

The economic incentives for herders in the pastoral region may be to produce sheepmeat rather than grow fine-wool, especially given the dramatic growth in meat demand in China. However, as Australia also has expertise to offer assistance in meat production, processing and distribution, then the scope for assistance, or the trade-offs considered in the negotiations, should not be confined to the wool market alone.

Australia could offer this assistance in return for Chinese commitments to maintain open import arrangements with respect to Australian wool.

Longworth and Brown (1995) highlight many areas where assistance could be provided. This assistance covers not only production and processing technology but also marketing services such as better commodity grading, testing and inspection procedures, information networks, and selling methods. For instance, bulk classing is one skill well developed in Australia and of particular relevance to the bulk of Chinese wool produced by small, geographically spread herders each with small heterogeneous lots of wool. Given the extensive agribusiness network of the Supply and Marketing Co-operatives, then efforts to help them develop bulk classing and other marketing services may not only improve domestic wool marketing in China but also appease groups supporting tighter wool import arrangements. And it presents commercial opportunities for Australian entrepreneurs. Similar strategic opportunities need to be explored with other Chinese institutions servicing the domestic wool industry such as the fibre inspection institutes that have inadequate and outdated equipment and poorly trained staff (Longworth and Brown 1995: Chapter 6) , and local wool scours which also suffer from poor equipment, poor management and an inability to optimally scour Australian wool (Brown and Longworth 1992) .

Australia has the expertise to assist China modernise and commercialise its wool industry and reform its agribusiness sector. However, in consideration and implementation of such a strategy, Australian negotiators and entrepreneurs need to be aware of the operation of other policy "mirages" in terms of a divergence between national strategies and local implementation. These divergences arise, among other reasons, because of the autonomy of local governments in China and that local governments often have shorter term objectives and planning horizons than the Central government (Longworth et al . 1997) . For instance, Australia is well placed to assist Chinese efforts to improve wool fibre inspection, sorting and grading. However, attempts to introduce a new raw wool purchasing standard in China at the end of 1993 illustrate the problem of reconciling national policies with local implementation.

Despite claims by the Central government of universal application of the new standard throughout the country, there remain many areas throughout the pastoral region which still use the old standard. Similarly, local autonomy and short-term planning horizons have implications for the provision of overseas assistance. Local officials tend to seek projects which involve the installation of new equipment or some other tangible immediate benefit. Less tangible forms of foreign assistance such as improved grading systems and information networks are viewed with much less enthusiasm despite having larger, though longer term, benefits.

Trade differences and disputes with China pose real challenges for Australian exporters and trade negotiators who, in the past, have considered them too overwhelming. But an in-depth understanding of the political economy can lead to identification of strategies to advance the negotiations. Often this involves assisting adversely affected firms and sectors in China adjust to the new marketing and trade environment. As the case of wool illustrated, however, the type and form of any assistance provided needs to be carefully considered. Not only must the assistance be of benefit, but it must also be perceived to be of benefit by the relevant local level institutions in China. Only then can the fullest utilisation and impact of the assistance be assured and, from a trade negotiations perspective, the greatest political support be realised for that assistance.

Cognisance of the political and socio-economic factors in China is fundamental to the success of Australian firms entering the Chinese market. This so-called "policy intelligence" (Longworth 1993) provides the necessary information about the policy environment for firms to make informed decisions and to develop appropriate strategies. However, in their rush to be part of the dynamic Chinese market, firms often dispense with their traditional market intelligence and feasibility studies (Hartcher 1997) let alone be concerned with broader policy related information. Individual firms tend to be too narrowly focussed and myopic to consider the wider policy environment. Furthermore, policy intelligence requires a depth of analysis and access to a wide range of institutions not normally available to individual firms. The non-firm specific and longer-term nature of the information also means that individual firms will not perceive an immediate return on investment in research in this area. Thus the policy intelligence discussed in this paper exhibits the classic features of a public good, and individual firms are likely to under-invest in this type of research even though it may be essential to their continued presence in the market. The case for government involvement in policy intelligence is strengthened when its importance in helping design appropriate trade negotiating strategies is considered.

Government involvement has already been evident in a number of ways. High level visits are an attempt to smooth relations and create a favourable trade environment. Furthermore, Federal and State governments have increased the number and sophistication of their general market reports on China. The recent report (Commonwealth of Australia 1997) by the East Asia Analytic Unit within the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade is a clear example. A mass of detailed information on the Chinese market, this report is a must for all Australian firms considering entering the market. But the suggestion of this paper is that these efforts need to be extended much further. In particular, many of the government reports and research to date have focussed on macro issues that impact on all trade. However, each commodity market and commodity trade has its own special characteristics and its own set of socio-economic and political factors which impact on decision making and firm behaviour. If the full nuances of any particular trade are to be comprehended, then in-depth policy intelligence needs to be carried out for specific commodity markets.

Policy intelligence research supports the normal market intelligence activities, not replace them. Individual Australian firms still need to establish direct commercial links with their Chinese counterparts, undertake market surveys and feasibility studies, and plan and organise their operations. However, the policy intelligence will give them the necessary insights into aspects such as which firms to contact and liaise with, what issues to be aware of, and the rules and administration of the rules of the market they are operating in. In short, it will allow them to make their trade, investment and commercial decisions with a much better comprehension of the policy environment in which these decisions will be made. This is important in any trade and in any country, but especially so in the case of China.

Some industries have become more attuned to the need for policy intelligence and a more sophisticated approach to the Chinese market. The wool industry itself has invested considerable effort in the 1990s with various reports (see, for example, IWS 1995) , a greater industry presence in China, and assistance with the modernisation and commercialisation of the Chinese wool industry. But this occurred only after the disastrous experiences of the late 1980s, and after a good deal of prodding. And it is debateable whether these efforts are sufficient. The concern is that many other industries have done much less, and that problems will emerge as their trade and industry gears up on a much more volatile customer, namely China. In essence, many of the industries associated with emerging commodities in Sino-Australian trade seem not to have noticed the lessons learnt the hard way by the wool industry.

Another area where lessons appear not to have been heeded and where policy intelligence may be particularly useful is trade negotiations. Negotiators need to take heed of existing policy intelligence or initiate studies where such information is not available. All too often, and whether it be imports of wool, live cattle or elaborately transformed manufactures, trade negotiations focus on technical aspects such as product specification and characteristics or veterinary protocols as these are the stated or notional barriers to trade. Often the barriers to trade, however, have much less to do with these technical issues than they do with socio-economic and political factors. Only with a complete understanding of these factors are trade negotiations likely to be advanced and the full potential of Sino-Australian trade realised.

Brown, C.G . and Longworth, J.W. (1992) 'Reconciling national economic reforms and local investment decisions in China: fiscal decentralisation and first stage wool processing' Development Policy Review 10: 389-402.

Brown, C.G. and Longworth, J.W. (1994) 'Lifting the wool curtain: recent reforms and new opportunities in the Chinese wool market with special reference to the up-country mills' Review of Marketing and Agricultural Economics 62(3): 369-387.

Brown, C.G. and Longworth J.W. (1995) 'Wool: China, Change and Trade' Current Affairs Bulletin 72(2): 4-13.

Chisholm, T ., Haszler, H., Edwards, G. and Hone, P. (1994) The wool debt, the wool stockpile and the national interest: did Garnaut get it right? Paper presented to the 38th Annual Conference of the Australian Agricultural Economics Society, Wellington.

Commonwealth of Australia (1997) China Embraces the Market: Achievements, Constraints and Opportunities , East Asia Analytic Unit, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Canberra.

Garnaut, R ., Bennett, S. and Price, R. (1993) Wool: Structuring for Global Realities: Report of the Wool Industry Review Committee , Department of Primary Industries and Energy, Canberra.

Hartcher, P. (1997) 'Firms need to do more homework on China', The Australian Financial Review , April 22, p. 11.

IWS (International Wool Secretariat) (1995) China: Raw Wool Importing and Early Stage Processing - Impediments to Business , International Wool Secretariat, Melbourne.

Longworth , J.W. (1993) 'Understanding our customers: hidden socio-political realities in Japan and China which influence trade with Australia' Australasian Agribusiness Review 1(1), 23-30.

Longworth, J.W. and Brown, C.G. (1995) Agribusiness Reform in China: The Case of Wool , C.A.B. International, Wallingford.

Longworth, J.W. and Williamson, G.J. (1993) China's Pastoral Region: Sheep and Wool, Minority Nationalities, Rangeland Degradation, and Sustainable Development , C.A.B. International, Wallingford.

Longworth, J.W., Brown, C.G., and Williamson, G.J. (1997) ' "Second generation" problems associated with economic reform in the pastoral region of China' International Journal of Social Economics , 24, 139-159.

Lin, X . (1993) 'The outlook for Chinese wool production and marketing: some policy proposals' in Longworth J.W. (ed.) Economic Aspects of Raw Wool Production and Marketing , ACIAR Technical Report No. 25, Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research, Canberra.

|